Tektites

TEKTITES

AND OTHER IMPACT-RELATED MATERIAL

left to right and top to bottom:

Quiongshan, Hainan, China (Guang Dong-type, 23.1 g)

Muong Nong, Thailand (Muong Nong-type, layered, 43.4 g)

Mt. Dare, S. Australia (AustraliteTektites found in Australia and are part of the Australasian Tektite Field, a region extending as far as Sri Lanka to the West, Tasmania Australia to the South, Philippines to the East and Southern China to the North. Australites were deposited 0.79 Ma ago by a massive impact that rained Click on Term to Read More, button/lens-shaped, 2.7 g)

Dalat, Vietnam (Indochinite, 13.0 g)

Boyaca, Columbia (Calitite [formerly Colombianite; see description below], 6.9 g)

Libyan Desert GlassHigh-silica glass (SiO2) found in western Egypt near the Libyan border. The glass is often worn smooth due to aeolian sandblasting and ranges in color from milky white to the gem quality translucent yellow-green. The glass often contains small bubbles and lechatelierite. The origin of the glass is still disputed, Click on Term to Read More (Desert Glass, 26.7 g) It is commonly accepted that tektites, a word derived from the Greek ‘molten’, formed from vaporized terrestrial rock following a hypervelocity impact on Earth. One could think of tektites as meteorites from Earth in the sense that they were blasted from the Earth through impact and shaped by aerodynamic forces as they plummeted back through the atmosphere to create defined strewn fields. Previous theories espousing an origin from volcanicIgneous rock that forms from cooling magma on the surface of a planet or asteroid. eruptions on the Moon have been adequately disputed through comparative studies of the chemistry and mineralogy of lunar samples returned from the Moon by the Apollo astronauts. Hydrocode simulations of impacts (Artemieva, 2001) have demonstrated that high-velocity impacts (35–40 km/s) having impact angles of 30° to 50° from the horizon, and impacting dry target material, are consistent with model constraints on tektiteNatural, silica-rich glasses produced by melting of target rocks and dispersal as droplets during terrestrial impact events. In contrast to most impact glasses, which are found inside or within the immediate vicinity of impact structures, tektites are distal impact ejecta. They range in color from black or dark brown to production. LechatelieriteAn amorphous silica glass formed naturally by the heat of impact/detonation of a large meteorite on/over quartz sand. Lechatelierite is found as an inclusion in Libyan Desert Glass. Most commonly formed during lightning strikes in sand. Named for Henry Louis Le Chatelier (1850-1936), a French chemist. Click on Term to Read More, a form of fused quartzComposed of SiO2, quartz is one of the silica group minerals most common in Earth's crust, but never found in meteorites as inclusions visible to the naked eye. Quartz in meteorites has been found in very small quantities in eucrites, other calcium-rich achondrites, and in the highly reduced E chondrites1. Click on Term to Read More, and other relict mineralInorganic substance that is (1) naturally occurring (but does not have a biologic or man-made origin) and formed by physical (not biological) forces with a (2) defined chemical composition of limited variation, has a (3) distinctive set of of physical properties including being a solid, and has a (4) homogeneous Click on Term to Read More inclusions showing evidence of shock metamorphismMetamorphism produced by hypervelocity impact between objects of substantial size moving at cosmic velocity (at least several kilometers per second). Kinetic energy is converted into seismic and heat energy almost instantaneously, yielding pressures and temperatures far in excess those in normal terrestrial metamorphism. On planetary bodies with no atmosphere, smaller Click on Term to Read More, are found inside tektites, consistent with an impact origin rather than one based on igneous volcanism. Moreover, the high-pressure polymorph of quartz known as coesiteHigh-pressure polymorph of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Has the same chemical composition as cristobalite, stishovite, seifertite and tridymite but possesses a different crystal structure. Coesite forms at intense pressures of above about 2.5 GPa (25 kbar) and temperature above about 700 °C, and was first found naturally on Earth in impact Click on Term to Read More has been identified in tektites, indicating pressures greater than 2 GPa. Elemental abundance patterns, along with size and shape characteristics of the mineral inclusions, suggest that the typical parent material for tektites was a terrestrial, fine-grained, sedimentary deposit similar to a graywacke or loessAn unconsolidated, clay-rich sediment deposited by the wind. Click on Term to Read More. One revealing fact in the tektite origin debate is that no unique tektites have ever been found in Antarctica, where meteorites from most all classes have previously been recovered, including many lunar specimens. A major point of contention held by the lunar-origin theorists (Futrell and O’Keefe, 1997) has been the very low content of water in tektites compared to the terrestrial source rock. A recent study into the physics and chemistry of impact-induced melting and vaporization explains this lack of water as a natural outcome of the thermodynamics associated with shock pressures in excess of 100 GPa and temperatures in excess of 50,000°C. Under these conditions, volatile-containing bubbles would carry all of the water vapor out of the silicateThe most abundant group of minerals in Earth's crust, the structure of silicates are dominated by the silica tetrahedron, SiO44-, with metal ions occurring between tetrahedra). The mesodesmic bonds of the silicon tetrahedron allow extensive polymerization and silicates are classified according to the amount of linking that occurs between the droplets, along with free oxygenElement that makes up 20.95 vol. % of the Earth's atmosphere at ground level, 89 wt. % of seawater and 46.6 wt. % (94 vol. %) of Earth's crust. It appears to be the third most abundant element in the universe (after H and He), but has an abundance only Click on Term to Read More, leading to reductionOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More of Fe and the formation of the dark green to black colors associated with tektites. Furthermore, lunar rocks contain still less water than tektites do. Most tektite strewn fields have now been associated with a particular impact structure with an established age directly relating the tektite to its corresponding ejectaFractured and/or molten rocky debris thrown out of a crater during a meteorite impact event, or, alternatively, material, including ash, lapilli, and bombs, erupted from a volcano. Click on Term to Read More deposit: Moldavites with the Ries CraterBowl-like depression ("crater" means "cup" in Latin) on the surface of a planet, moon, or asteroid. Craters range in size from a few centimeters to over 1,000 km across, and are mostly caused by impact or by volcanic activity, though some are due to cryovolcanism. Click on Term to Read More in Germany, Ivory Coast tektites with the Bosumtwi crater in Ghana, and the North American tektites with the Chesapeake Bay Impact CraterCrater formed by high-speed impact of a meteoroid, asteroid, or comet on a solid surface. Craters are a common feature on most moons (an exception is Io), asteroids, and rocky planets, and range in size from a few cm to over 1,000 km across. There is a general morphological progression Click on Term to Read More. The largest known strewnfield, represented by the Austalasian tektites, has yet to be identified with a particular impact structure, and it has been suggested that this event might reflect an aerial burst similar to the event over Tunguska, Siberia, and that which produced Libyan Desert Glass in Egypt. However, geochemical data suggest that these tektites sample typical post-Archean sedimentary, upper crustal rocks. Analyses of Australasian microtektites by Folco et al. (2017, #6036), based on Co/Ni vs. Cr/Ni, revealed a chondritic signature most similar to LL chondritesChondrites are the most common meteorites accounting for ~84% of falls. Chondrites are comprised mostly of Fe- and Mg-bearing silicate minerals (found in both chondrules and fine grained matrix), reduced Fe/Ni metal (found in various states like large blebs, small grains and/or even chondrule rims), and various refractory inclusions (such Click on Term to Read More with an admixture of terrestrial material. This is inconsistent with an airburst model and indicates that this was a cratering event. GravityAttractive force between all matter - one of the four fundamental forces. Click on Term to Read More and topography data from Seasat and Geosat has identified an ~100-km circular feature off the coast of Vietnam in the South China Sea centered at 13.6° N., 110.5° E., which could prove to be the elusive crater. Other searches have been conducted in Guangdong and Guangxi provinces in South China utilizing satelliteBody in orbit (such as a moon) around another larger body (such as a planet or star). Click on Term to Read More imagery. By this method, a complex structure measuring 25–30 km in diameter has been identified which may be associated with the Australasian tektites (Kenkmann et al., 2014). Designated ‘Zaotang’, the structure is centered at 25° 56′ 16′ N., 111° 36′ 30′ E.; in Hunan province; furthur investigations are needed to verify a relationship. Recoveries of some Indochinite tektites with signs of stretching during flight provide more evidence for an impact origin rather than an extraterrestrial origin. If these features had been the result of etching by soil acids, as some have argued, the stretch areas would have been etched to a similar degree as the rest of the tektite, which is not the case. This leads to the conclusion that these features were formed by aerodynamic sculpting instead. The internal heating demonstrated by the plastic stretching is also further evidence that the tektites did not arrive on Earth as individuals, in which case the only heating effects would be those on the exterior caused by heating during entry. Instead, these features were the result of spallationThe formation of new nuclides by interactions of high-energy cosmic ray protons with target nuclei that commonly produce several smaller product nuclides. on a large, rapidly rotating body within the atmosphere. The photo above shows four members of the ~790 t.y.-old Australasian strewn fieldArea on the surface containing meteorites and fragments from a single fall. Also applied to the area covered by tektites, which are produced by large meteorite impacts. Strewnfields are often oval-shaped with the largest specimens found at one end. Given that the largest specimens go the greatest distance, a meteoroid's, which covers at least one-tenth of the Earth’s surface. Transantarctic Mountain microtektites, in the form of microscopic, pale-yellow to pale-green, transparent glassy spherules, likely represent the southern-most extent of the Australasian tektite strewn field (Folco et al., 2009). Other tektite sources likely represented by this strewn field include those from Tibet, the Phillipines (Rizalite, Bikolite, Anda) and Java. Based on the spatial variation in microtektite concentrations determined from deep-sea drilling sediment cores, as well as the variation in size and in the microimpact features along a North–South transect covering a distance of 1,300 km in the Central Indian Ocean, a possible location for the source crater is thought to be in eastern Cambodia (12° N., 106° E.), in agreement with previous predictions (Prasad et al., 2007, 2010). Conversely, Whymark (2013) reviewed the current state of the evidence for this event, including macro- and micro-tektite distribution, crater ray alignment, and chronological/isotopic data, and it was concluded that the fallMeteorite seen to fall. Such meteorites are usually collected soon after falling and are not affected by terrestrial weathering (Weathering = 0). Beginning in 2014 (date needs confirmation), the NomComm adopted the use of the terms "probable fall" and "confirmed fall" to provide better insight into the meteorite's history. If Click on Term to Read More likely occurred in the Gulf of Tonkin, possibly within the Song Hong-Yinggehai (SHY) Basin. The diameter of the source crater was previously estimated to be 17–114 km, and after further refinement, ~40 km. Consistent with this, an ~43 km circular feature having rings extending to ~90 km has been detected in the SHY Basin (17°45’20’ N, 107°50’30’ E). An issue that remains unresolved concerns the origin of the kinetic energy required to produce the flange flattening of australite button-form tektites. An atmospheric reentry speed of ~10 km/s was experimentally calculated by Chapman and Larson (1962) to reproduce this particular tektite morphology. However, after considering the loss of energy due to shock vaporization during ejection, about half of this value (or ¾ of the launch kinetic energy) remains unaccounted for. Furthermore, given the ~10 km/s australite reentry speed, a minimum suborbital flight duration (Time Of Flight) of ~3.25 hours was calculated by Thomas H. S. Harris (archived publications, which would necessarily result in a landing point ~32,000 km from the source due to Earth’s rotation; this is inconsistent with the known geographic distribution of ejecta and rules out a launch site in Indochina, or even from within the same hemisphere. Notably, calculations for microtektites indicate significantly longer loft times, which makes Earth’s rotation an even greater factor in the longitudinal aspect. In the 2015 paper ‘Suborbital Imprint Matching’, Thomas H. S. Harris proposes an alternative origin for the Austalasian tektites in North America. He demonstrates that an oblique impact during the Quaternary/Pleistocene Ice Age (2.58 m.y. ago to the present) onto the North American Laurentide ice sheet covering quartz sediments is more consistent with orbital analyses and other data related to these tektites. He further argues that adiabaticProcess in which no heat enters or leaves a system. This is the case, for example, when an interstellar gas cloud expands or contracts. Adiabatic changes are usually accompanied by changes in temperature or volume. Click on Term to Read More water vapor expansion in the form of steam or plasmaFourth state of matter: a gas in which many or most of the atoms are ionized. In the plasma state the atoms have split into positive ions and negative electrons, which can flow freely, so the gas becomes electrically conducting and a current can flow. Click on Term to Read More arising from such an impact can account for the remaining energy contributing to tektite suborbital flight, and can also explain the uniform iron oxidationOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More state of the tektites. It was posited by Harris (2016) that an impact onto an extensive ice sheet resulted in the shock-melting of quartz substrate and the disassociation of water under electromagnetic conditions which supported the prolonged availability of oxygen ions, thus promoting the uniform Fe oxidation observed in the tektites. In addition, Harris observed that the ~1,600 km³ Carolina Bays sand unit, which covers ~5% of the continental U.S., shows depositional features (e.g., ovoid shape with latitude-dependent axes possibly associated with Coriolis force) consistent with suborbital transport and densityMass of an object divided by its volume. Density is a characteristic property of a substance (rock vs. ice, e.g.). Some substances (like gases) are easily compressible and have different densities depending on how much pressure is exerted upon them. The Sun is composed of compressible gases and is much Click on Term to Read More impedance processes. The age of the Carolina Bays have been calculated to be between 140 t.y. and 1.6 m.y., which encompasses the age of the Australasian tektites.

A suspect ejecta blanketGenerally symmetrical apron of ejecta surrounding a crater; it is thick at the crater's rim and thin to discontinuous at the blanket's outer edge. Click on Term to Read More imaged with LIDAR, showing a portion of 45,000+ co-aligned sand bed voids scaling from 100 meters to several kilometers,

aligned systematically by latitude, with robust adherance to only 6 different archetype ovoid shapes, which are now referred to as ‘Davias archetypes’ by investigators. Image credit: M. Davias—Cintos Research; Caption credit: Thomas H. S. Harris (2015), ‘Suborbital Deconvolution Of Ejecta And Strewn’ A correlated cosmic impact origin for the Australasian tektites (and certain other tektites), the Carolina Bays, and an elongated, oval, ‘thumb-like’ depression in Saginaw Bay, Michigan (historically attributed to glacial erosionRemoval of weathered rocks by moving water, wind, or ice. Click on Term to Read More), has been conjectured by Davias and Harris (2015) in ‘A Tale Of Two Craters: Coriolis-Aware Trajectory Analysis Correlates Two Pleistocene Impact Strewn Fields And Gives Michigan A Thumb’. Their hypothesis is supported by forensic evidence (e.g., target rock composition, zirconOrthosilicate mineral, Zr(SiO4), observed in all terrestrial rocks type and in ordinary chondrites, eucrites, mesosiderites, and lunar rocks. age) and sub-orbital calculations.

An example martian oblique impact crater with a butterfly-shaped ejecta blanket overlain on a Google image of Saginaw Bay

GIF images courtesy of Michael E. Davias—‘Correlating the Orientation of Carolina bays to a Cosmic Impact’

mouseover the time machine set to 785 t.y. before present Schwarz et al. (2013) obtained Ar–Ar ages for the Australasian tektites and the tektite-like melt glass samples recently discovered in Western Canada and Belize. Their results indicated that all of these objects formed at the same time within uncertainties 785 (±7) t.y. ago, but that the chemical composition of the Belize tektite-like glass was distinct from tektites/melt glass from the other two locations. Thereafter, Schwarz et al. (2016) conducted more precise Ar–Ar measurements of these various objects, and they determined that the Australasian tektites and the compositionally similar Western Canadian tektite-like glass have indistinguishable ages of 785 (±7) t.y., indicating that they formed during the same impact event. By comparison, they found that the compositionally different tektite-like glass samples from Belize have a younger age of 769 (±16) t.y., indicating that these objects formed during an earlier, separate impact event. The button/lens-shaped Australite above, which was the first type of tektite described in the literature by naturalist Charles Darwin, exhibits typical concentric ring-wave flow ridges on the forward face emanating from the stagnation point, consistent with aerodynamically stable hypervelocity ablationGradual removal of the successive surface layers of a material through various processes. • The gradual removal and loss of meteoritic material by heating and vaporization as the meteoroid experiences frictional melting during its passage through the atmosphere. The resulting plasma ablates the meteor and, in cases where a meteor Click on Term to Read More during descent. The Muong Nong-type layered tektites are thought to have formed close to the source crater, consistent with their lack of ablation features and a recovery location very near that predicted for the source crater. The last photo shown above is a mass of Libyan desert glass (LDG), melted silicaSilicon dioxide, SiO2. glass thought to have been formed by an asteroid impact in the Great Sand Sea region of western Egypt ~28.5 m.y. ago. In contrast to the commonly accepted scenario of a near-surface airburst, the occurrence of an asteroid impact with consequent heating to temperatures of ~1550°C and the simultaneous formation of lechatelierite and cristobaliteHigh temperature polymorph of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Has the same chemical composition as coesite, stishovite, seifertite and tridymite but possesses a different crystal structure. This silica group mineral occurs in terrestrial volcanic rocks, martian and lunar meteorites, chondrites and impact glasses like Libyan Desert Glass. Cristobalite has a very open Click on Term to Read More is supported by the presence of brownish inclusions of a molten low-Ca, Al-rich orthopyroxeneOrthorhombic, low-Ca pyroxene common in chondrites. Its compositional range runs from all Mg-rich enstatite, MgSiO3 to Fe-rich ferrosilite, FeSiO3. These end-members form an almost complete solid solution where Mg2+ substitutes for Fe2+ up to about 90 mol. % and Ca substitutes no more than ~5 mol. % (higher Ca2+ contents occur Click on Term to Read More target rock, as well as by the incorporation of deep-seated terrestrial material (Greshake et al., 2010). Shock metamorphosed sandstones are also consistent with this impact scenario, although O-isotopic analysis found that the target rocks consisted of quartz sands derived from intrusives of Pan-African age (Longinelli et al., 2011). Another study of C and Cl in Libyan desert glass reveals quenching upon impact of a carbon-rich projectile with silica-rich crustal rocks and sea-water rather than an impact on dry land (Miura, 2009). It has been estimated that at least 10 million tons of LDG were created in a layer up to a few mm thick extending over an area of 6,500 km², from which 20 tons has been collected (Pratesi et al., 2002; Greshake et al., 2010). A small, extensively weathered fragment of oxidizedOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More iron showing remnants of an octahedral structure (named Great Sand Sea 003) is possibly associated with this event. Although a meteoritic component of ~0.5% has been previously identified in LDG, dark streaks with nonchondritic elemental ratios represent terrestrial material. The energy released during this explosion is calculated to have been equivalent to that of the Tunguska event. Resulting high-temperature melt-products identified in LDG glass include lechatelierite and cristobalite from quartz, and baddeleyiteA rare zirconium oxide (ZrO2) mineral, often formed as a shock-induced breakdown product of zircon. This mineral can be found in some lunar and martian meteorites. Click on Term to Read More from zircon. CathodoluminescenceEmission of visible light in response to electron bombardment. Click on Term to Read More imaging has identified previously unrecognized quenched flow textures in this glass, potentially useful for characterizing the temperature of formation (Gucsik et al., 2003); temperatures in the 1700–2100°C range have now been calculated (Pratesi et al., 2002). These rare brown to bluish (from Rayleigh scattering by 60 nm-sized or smaller particles) streaks have been resolved into discrete rounded glass spherules which constitute an immiscibleThe property of liquids that are mutually insoluble (won't mix together) such as oil and water or metallic and silicate melts. Click on Term to Read More liquid within the silica-glass matrixFine grained primary and silicate-rich material in chondrites that surrounds chondrules, refractory inclusions (like CAIs), breccia clasts and other constituents. Click on Term to Read More. These spherules are enriched in Al, Fe, and Mg, as well as Ir, Os, Cr, Co, and Ni, elements which may reflect a significant meteoritic component. GraphiteOpaque form of carbon (C) found in some iron and ordinary chondrites and in ureilite meteorites. Each C atom is bonded to three others in a plane composed of fused hexagonal rings, just like those in aromatic hydrocarbons. The two known forms of graphite, α (hexagonal) and β (rhombohedral), have Click on Term to Read More ribbons, possibly derived from the impactor, have also been identified. Brecciated sandstone samples from the LDG area show signs of fractures, mosaicism, undulatory extinctionIn astronomy, the dimming of starlight as it passes through the interstellar medium. Dust scatters some of the light, causing the total intensity of the light to diminish. It is important to take this effect into account when measuring the apparent brightness of stars. The dark bands running across portions Click on Term to Read More, and cleavage. Planar deformation features and other shock features provide persuasive evidence for a hypervelocity impact origin. Geochronological data and isotopic ratios of Sr and Nd indicate that the target material was sand, derived from Precambrian crustal granitic rock, rather than Lower Cretaceous sandstones of the Nubia Group. The photo shown below is an artifact recovered from King Tutankhamun’s tomb. This pectoral fearures a yellow-green gem in the image of a scarab, carved from a piece of Libyan Desert Glass. This demonstrates the special nature of this material to the early Egyptian civilization.

Similar to LDG, the high-silica Dakhleh Glass (DG) from the Dakhleh Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt, probably derives from a low-altitude airburst ~120 (±40) t.y. ago into Pleistocene lacustrine sediments (Osinski et al., 2008). Many of the black to dark-gray DG specimens are vesiculated on the upper surface, sometimes exhibiting impressions of grass and reed vegetation on the underside, some containing burnt sediments. Dakhleh Glass is predominantly a mixture of glass and crystallites.

Pictured below is an olive-green, filigree-like moldaviteTektite type whose name is derived from the Moldau (Vltava) river in the Czech Republic where the first pieces were identified. The vast majority of moldavites originate from the Czech Republic where they are mined. Moldavites are generally translucent with extensive etching, and forest green to olive green in color. Click on Term to Read More, a member of the Central European strewn field associated with the 14.68 (±0.11) m.y. old, 24-km-wide Nördlinger Ries impact crater in Germany (Laurenzi et al., 2003; Vincenzo and Skála, 2008). The 3.8-km-wide Steinheim Basin crater, located 42 km west-southwest of the Ries crater, is considered to have been formed during the same event, attesting to a binary asteroid impact. Through 3-D hydrocode simulations (Stöffler et al., 2002), it was determined that the two impact projectiles, with diameters of 1.5 km and 0.15 km, impacted at an angle of 30–50° from the horizontal at a velocity of ~20 km/s. The leading shock waveAbrupt perturbation in the temperature, pressure and density of a solid, liquid or gas, that propagates faster than the speed of sound. impacted the target material, consisting of both weathered and unweathered, unconsolidated, Middle Miocene silica-rich sands, with lesser amounts of clays and carbonates, generating temperatures of ~40,000°C (Skála et al., 2009). The superheated melt was distributed up to 400–500 km away in a symmetrical, ~60° fan-shaped jet, the remnant of which today is represented by the moldavite strewnfields of South Bohemia, Moravia, the Cheb Basin, northern Austria, and Lusatia. Rapid cooling and solidification of the melt ensued, leading to the formation of tektites.

Moldavites accumulated from melt particles of variable chemical composition. The ultimate shape of moldavites is a result of etching by groundwater in an acidic, permeable environment. They are virtually water-free and incorporate cations that reflect differentiationA process by which a generally homogeneous chondritic body containing mostly metal, silicates and sulfides will melt and form distinct (differentiated) layers of different densities. When the melting process continues for a long enough period of time, the once chondritic body will re-partition into layers of different composition including Click on Term to Read More based on ionic size, a result of their formation (fractional condensation) at plasma temperatures (von Engelhardt et al., 2005). Shock forces from the Ries impact created shattercones in the limestoneA common form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Other common forms of CaCO3 include chalk and marble. Click on Term to Read More layer below.

Similar to LDG, the high-silica Dakhleh Glass (DG) from the Dakhleh Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt, probably derives from a low-altitude airburst ~120 (±40) t.y. ago into Pleistocene lacustrine sediments (Osinski et al., 2008). Many of the black to dark-gray DG specimens are vesiculated on the upper surface, sometimes exhibiting impressions of grass and reed vegetation on the underside, some containing burnt sediments. Dakhleh Glass is predominantly a mixture of glass and crystallites.

Pictured below is an olive-green, filigree-like moldaviteTektite type whose name is derived from the Moldau (Vltava) river in the Czech Republic where the first pieces were identified. The vast majority of moldavites originate from the Czech Republic where they are mined. Moldavites are generally translucent with extensive etching, and forest green to olive green in color. Click on Term to Read More, a member of the Central European strewn field associated with the 14.68 (±0.11) m.y. old, 24-km-wide Nördlinger Ries impact crater in Germany (Laurenzi et al., 2003; Vincenzo and Skála, 2008). The 3.8-km-wide Steinheim Basin crater, located 42 km west-southwest of the Ries crater, is considered to have been formed during the same event, attesting to a binary asteroid impact. Through 3-D hydrocode simulations (Stöffler et al., 2002), it was determined that the two impact projectiles, with diameters of 1.5 km and 0.15 km, impacted at an angle of 30–50° from the horizontal at a velocity of ~20 km/s. The leading shock waveAbrupt perturbation in the temperature, pressure and density of a solid, liquid or gas, that propagates faster than the speed of sound. impacted the target material, consisting of both weathered and unweathered, unconsolidated, Middle Miocene silica-rich sands, with lesser amounts of clays and carbonates, generating temperatures of ~40,000°C (Skála et al., 2009). The superheated melt was distributed up to 400–500 km away in a symmetrical, ~60° fan-shaped jet, the remnant of which today is represented by the moldavite strewnfields of South Bohemia, Moravia, the Cheb Basin, northern Austria, and Lusatia. Rapid cooling and solidification of the melt ensued, leading to the formation of tektites.

Moldavites accumulated from melt particles of variable chemical composition. The ultimate shape of moldavites is a result of etching by groundwater in an acidic, permeable environment. They are virtually water-free and incorporate cations that reflect differentiationA process by which a generally homogeneous chondritic body containing mostly metal, silicates and sulfides will melt and form distinct (differentiated) layers of different densities. When the melting process continues for a long enough period of time, the once chondritic body will re-partition into layers of different composition including Click on Term to Read More based on ionic size, a result of their formation (fractional condensation) at plasma temperatures (von Engelhardt et al., 2005). Shock forces from the Ries impact created shattercones in the limestoneA common form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Other common forms of CaCO3 include chalk and marble. Click on Term to Read More layer below.

The four photos below represent tektites from the two remaining recognized strewnfields, along with an impact glass similar in composition to the LDGs:

The four photos below represent tektites from the two remaining recognized strewnfields, along with an impact glass similar in composition to the LDGs:

- (top) Georgiaite, 15.9 g, one of ~2700 Georgia area tektites of the North American strewnfield with an age, location, and source rock composition consistent with an origin from the ~33–34.5 m.y. old (Fernandes et al., 2012), ~40-km-wide Chesapeake Bay impact structure.

- (top center) Bediasite, 26.7 g, along with Georgiaites, these are the oldest tektites known. While Georgiaites are found in 24 counties in east central Georgia and 2 in western South Carolina, Bediasites are found in 9 counties in southeast Texas and are characterized by their darker shade of green and their deeply grooved and etched surfaces resembling the Rizalites of the Philippines. Bediasites were propelled 1,300 miles from the impact site, landing in Eocene sediments where they are now being slowly eroded out along a narrow band in central Texas.

- (bottom center) Ivory Coast, 14.6 g, a member of the Ivory Coast strewnfield, from the 1.07 m.y. old, 10.5-km-wide Bosumtwi crater in Ghana. These have the lowest water contents of all tektites measured. Osmium isotopic ratios within these tektites are much higher than continental crustOutermost layer of a differentiated planet, asteroid or moon, usually consisting of silicate rock and extending no more than 10s of km from the surface. The term is also applied to icy bodies, in which case it is composed of ices, frozen gases, and accumulated meteoritic material. On Earth, the Click on Term to Read More values, evidence of a relict meteoritic component. Low rhenium isotopic ratios are the result of fractionationConcentration or separation of one mineral, element, or isotope from an initially homogeneous system. Fractionation can occur as a mass-dependent or mass-independent process. Click on Term to Read More that occurred during the impact.

- (bottom) Irghizite, 1.8 g, an impact glass from the ~0.8 m.y. old, 13.5-km-wide Zhamanshin crater in Kazakhstan. These glasses were formed at the impact site as flows and incorporate both terrestrial and meteoritic components. Examination of vesicles within Irghizites has revealed the presence of organosilane and organosiloxane, compounds never before found in nature. They are thought to have formed under intense heat and reducingOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More conditions through interactions of a high-silica melt with hydrocarbons. Also associated with the Zhamanshin crater are the Zhamanshinites, but they are larger and have a more blocky shape than their Irghizite cousins. In contrast to Irghizites, Zhamanshinites are thought to have formed in the cooler melt regions at the outer rim and did not retain a meteoritic component.

Still other impact glasses have been found to be associated with craters:

Still other impact glasses have been found to be associated with craters:

- (top) Aouelloul glass, 0.95 g, associated with a 3.1 m.y. old, 390-m-wide crater in the Adrar region of the Western Sahara Desert in Mauritania. Lechatelierite and baddeleyite are present in the glass as well as an extraterrestrial component. Through BSE and CL imaging it was found that the degree of homogenization attests to a lower temperature formation of Aouelloul glass than for Libyan desert glass (Gucsik et al., 2004).

- (bottom) Darwin glassImpact glass found in the environs of the 1.2 km-diameter Darwin impact crater in western Tasmania, Australia. Click on Term to Read More, 1.64 g, with an 40Ar/Ar39 age of ~816 t.y., associated with a 1.2 km diameter impact crater in southwest Tasmania, Australia. On a geologic time scale, the Darwin impact occurred coincident with the Australasian impact (~803 t.y.), but the two events were separated by several thousand km. Relative to its size, Darwin crater is the source of the largest volume of glass compared to other impact craters worldwide (Howard, 2009). This prodigious amount of glass is a direct result of the enhanced volatility caused by the high water content in the target stratigraphy. This vesiculated, layered, fragmental glass ranges in color from white (5%, located closest to the crater), light green (31%), dark green (53%), and black (11%, located farthest from the crater). In addition, five different shape categories have been distinguished: irregular, ropy, elongate, droplet, and spheroid. The light green, irregular-shaped sample shown below represents the most common shape (74%) among all colors. Heterogeneity among samples is indicative of rapid quenching of the melt, and metalElement that readily forms cations and has metallic bonds; sometimes said to be similar to a cation in a cloud of electrons. The metals are one of the three groups of elements as distinguished by their ionization and bonding properties, along with the metalloids and nonmetals. A diagonal line drawn Click on Term to Read More enrichment in some specimens likely reflects contamination by the impactor (Howard, 2008).

In addition to these, the Monturaqui glasses are associated with a ~100 t.y. old, 370-m-wide crater located in the Atacama Desert, Chile, and since 2012 thousands of small splash-form tektites (or impact glass) have been recovered in the central region of the Atacama Desert and termed ‘Atacamaites’, but no associated crater has yet been found (Devouard et al., 2014). Also, at least seven distinct horizons of impact glass have been identified in loess-like deposits of the Pampeano Formation of Argentina (Schultz et al., 2002, 2004):

In addition to these, the Monturaqui glasses are associated with a ~100 t.y. old, 370-m-wide crater located in the Atacama Desert, Chile, and since 2012 thousands of small splash-form tektites (or impact glass) have been recovered in the central region of the Atacama Desert and termed ‘Atacamaites’, but no associated crater has yet been found (Devouard et al., 2014). Also, at least seven distinct horizons of impact glass have been identified in loess-like deposits of the Pampeano Formation of Argentina (Schultz et al., 2002, 2004):

- Rio Cuarto impact glass dated to the Holocene Epoch at 6 (±2) t.y. ago

- impact glass sites dated to the Pleistocene Epoch at 114 (±26) t.y. ago

- impact glass sites dated to the Pleistocene Epoch at 230 (±30) t.y. ago

- glass impactites dated to the Pleistocene Epoch from Centinela del Mar at 445 (±11) t.y. ago

- impact glass sites dated to the Pleistocene Epoch near Necochea at 445 (±21) t.y. ago

- impact glass near Mar del Plata dated to the Pliocene Epoch at 3.27 (±0.08) m.y. ago

- impact glass near Buenos Aires Province dated to the Miocene Epoch at 5.33 (±0.05) m.y. ago

- impact glass near Chasico dated to the Miocene Epoch at 9.23 (±0.09) m.y. ago, which is associated with a concentric structure measuring 15 km in diameter

A unique Central American tektite-like glass strewn field has been established in western Belize, but recent finds have extended the area to encompass at least 6400 km² encompassing southern Mexico, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, San Salvador, and possibly Costa Rica (H. Povenmire et al., 2014; Koeberl and Schulz, 2016; H. Povenmire, 2016). While the first account of these tektite-like glass samples was published by A. Hildebrand et al. (1992), the first undisputed specimens to be authenticated by lab analyses were recovered by J. Cornec. Over 500 specimens exhibiting typical tektite-like morphologies and low water content (~80 ppmParts per million (106). Click on Term to Read More) are estimated to have been recovered thereafter, in large part as a result of three hunting expeditions led by B. Burrer. These objects often occur in clusters in newly cleared agricultural lands. A precise Ar–Ar age of 769 (±16) t.y. was determined by Schwarz et al. (2016), which is younger than the age of Australasian tektites. Moreover, the compositional (e.g., SiO2 contents) and isotopic differences (e.g., Sr–Nd, Os) that exist between the Australasian tektites and the Belize tektite-like glasses indicate that they represent separate impact events. Measurements of cosmogenic 10Be by Park et al. (2018) also support the assumption that Belize tektite-like glasses derive from a separate source from that of Australasian tektites (see chart below).

Chart credit: Park et al., 49th LPSC, #1296 (2018) The ~12-km-wide Pantasma Crater in northern Nicaragua has been identified as a possible source of the Belize tektite-like glass (Povenmire et al., 2011, 2012; Rochette et al., 2017). The Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopic compositions for 12 samples are more similar to terrestrial mantleMain silicate-rich zone within a planet between the crust and metallic core. The mantle accounts for 82% of Earth's volume and is composed of silicate minerals rich in Mg. The temperature of the mantle can be as high as 3,700 °C. Heat generated in the core causes convection currents in Click on Term to Read More values than to other tektites, and indicate that the impact source rock was either volcanic in origin or that these objects are actually volcanic glasses (Koeberl et al., 2015). Results from a combined Re–Os isotopeOne of two or more atoms with the same atomic number (Z), but different mass (A). For example, hydrogen has three isotopes: 1H, 2H (deuterium), and 3H (tritium). Different isotopes of a given element have different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus. Click on Term to Read More and platinum-group elementSubstance composed of atoms, each of which has the same atomic number (Z) and chemical properties. The chemical properties of an element are determined by the arrangement of the electrons in the various shells (specified by their quantum number) that surround the nucleus. In a neutral atom, the number of Click on Term to Read More analysis conducted by Koeberl and Schulz (2016) support the hypothesis of a local (Central American arc) volcanic origin for the precursor material without incorporation of an extraterrestrial component. With respect to their extensive database recording magnetic signatures of tektites, impactites, and various types of natural glasses, Hoffmann et al. (2016) found that the Belize tektite-like glasses are most similar to impactiteSlag-like glassy object found on surface of the Earth formed from rock melted by the impact of a meteor. This word is also applied to rocks that have been affected by impact (impact breccia, suevite, etc.) The backscattered electron photograph below shows the impactite’s complex internal structure. Click on Term to Read More glass. Photos of Belize specimens can be found in the article Belize Tektites by Brian C. Burrer, published in MeteoriteWork in progress. A solid natural object reaching a planet’s surface from interplanetary space. Solid portion of a meteoroid that survives its fall to Earth, or some other body. Meteorites are classified as stony meteorites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites. These groups are further divided according to their mineralogy and Click on Term to Read More Times Magazine (April 2011).

click on image for a magnified view

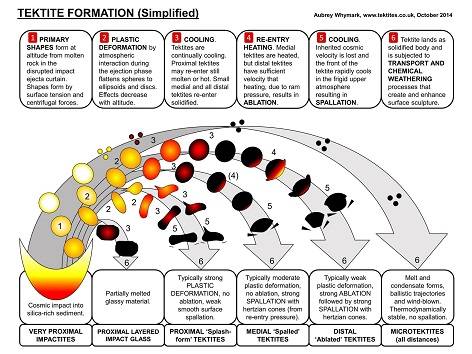

Image credit: Aubrey Whymark—tektites.co.uk