Iron, ungroupedModifying term used to describe meteorites that are mineralogically and/or chemically unique and defy classification into the group or sub-group they most closely resemble. Some examples include Ungrouped Achondrite (achondrite-ung), Ungrouped Chondrite (chondrite-ung), Ungrouped Iron (iron-ung), and Ungrouped Carbonaceous (C-ung). Click on Term to Read More

(silicated, possibly unique member of CR chondriteClass named for the Renazzo meteorite that fell in Italy in 1824, are similar to CMs in that they contain hydrous silicates, traces of water, and magnetite. The main difference is that CRs contain Ni-Fe metal and Fe sulfide that occurs in the black matrix and in the large chondrules Click on Term to Read More clan)

Found 1845

31° 51′ N., 110° 58′ W. Two masses of the Tucson meteoriteWork in progress. A solid natural object reaching a planet’s surface from interplanetary space. Solid portion of a meteoroid that survives its fall to Earth, or some other body. Meteorites are classified as stony meteorites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites. These groups are further divided according to their mineralogy and Click on Term to Read More were found, the ring-shaped Irwin–Ainsa mass and the paired, slab-shaped, Carleton mass. No fusion crustMelted exterior of a meteorite that forms when it passes through Earth’s atmosphere. Friction with the air will raise a meteorite’s surface temperature upwards of 4800 K (8180 °F) and will melt (ablate) the surface minerals and flow backwards over the surface as shown in the Lafayette meteorite photograph below. Click on Term to Read More or heat-affected zone remains on either mass. The meteorites consist of a refractory and reducedOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More mixture of fine-grained, Si–Cr-bearing FeNi-metal (92 vol%) and nearly alkali-free silicates (8 vol%), both having a nebular rather than an igneous origin; the FeNi-metal is considered to have condensed first.

The small (0.1–2 mm)

silicateThe most abundant group of minerals in Earth's crust, the structure of silicates are dominated by the silica tetrahedron, SiO44-, with metal ions occurring between tetrahedra). The mesodesmic bonds of the silicon tetrahedron allow extensive polymerization and silicates are classified according to the amount of linking that occurs between the inclusions occur as curvy-linear arrangements suggestive of a flow alignment. They consist primarily of forsteritic

olivineGroup of silicate minerals, (Mg,Fe)2SiO4, with the compositional endpoints of forsterite (Mg2SiO4) and fayalite (Fe2SiO4). Olivine is commonly found in all chondrites within both the matrix and chondrules, achondrites including most primitive achondrites and some evolved achondrites, in pallasites as large yellow-green crystals (brown when terrestrialized), in the silicate portion Click on Term to Read More (66.4%) with both pure and high-Al

enstatiteA mineral that is composed of Mg-rich pyroxene, MgSiO3. It is the magnesium endmember of the pyroxene silicate mineral series - enstatite (MgSiO3) to ferrosilite (FeSiO3). Click on Term to Read More (30.2%), with minor low- and high-Al

pyroxeneA class of silicate (SiO3) minerals that form a solid solution between iron and magnesium and can contain up to 50% calcium. Pyroxenes are important rock forming minerals and critical to understanding igneous processes. For more detailed information, please read the Pyroxene Group article found in the Meteoritics & Classification category. Click on Term to Read More (diopside, 2.7%), pure

anorthiteRare compositional variety of plagioclase and the calcium end-member of the plagioclase feldspar mineral series with the formula CaAl2Si2O8. Anorthite is found in mafic igneous rocks such as anorthosite. Anorthite is abundant on the Moon and in lunar meteorites. However, anorthite is very rare on Earth since it weathers rapidly Click on Term to Read More and

mesostasisLast material to crystallize/solidify from a melt. Mesostasis can be found in both chondrules, in the matrix around chondrules, and in achondrites as interstitial fine-grained material such as plagioclase, and/or as glass between crystalline minerals. Click on Term to Read More glass (0.7%), and trace

spinelMg-Al oxide, MgAl2O4, found in CAIs. and brezinaite (Nehru

et al., 1982 and references therein). It was determined that the olivine crystallized from a liquid, of which the latter is now present as glass inclusions within olivine grains.

Tucson is thought to have formed from a metal–silicate mixture that was co-precipitated from the

solar nebulaThe primitive gas and dust cloud around the Sun from which planetary materials formed. at high temperatures (~1500°C) and high pressures (~ >1

barUnit of pressure equal to 100 kPa.) under highly

reducingOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More and turbulent conditions. This was followed by rapid cooling (~1,000°C/m.y.) and annealing as evidenced by the high-Al pyroxene and the presence of quenched clear glasses, thus preserving the early-condensed, chondrule-like form of the silicate inclusions. The occurrence of rare Ca-rich

plagioclaseAlso referred to as the plagioclase feldspar series. Plagioclase is a common rock-forming series of feldspar minerals containing a continuous solid solution of calcium and sodium: (Na1-x,Cax)(Alx+1,Si1-x)Si2O8 where x = 0 to 1. The Ca-rich end-member is called anorthite (pure anorthite has formula: CaAl2Si2O8) and the Na-rich end-member is albite Click on Term to Read More in Tucson instead of the

alkali feldsparVariety of feldspar containing alkali metals potassium and sodium in a solid solution. A more complete explanation can be found on the feldspar group page that also includes the plagioclase feldspars as part of the feldspar ternary diagram. Click on Term to Read More present in most other silicated irons is consistent with

volatileSubstances which have a tendency to enter the gas phase relatively easily (by evaporation, addition of heat, etc.). loss during high temperature conditions (Ruzicka, 2014 and reference therein). Due to this rapid cooling, no Thomson (Widmanstätten) structure is present upon etching, and Tucson is classified structurally as an

ataxiteWork in Progress Relatively rare variety of iron meteorite (designated type D) made almost entirely of taenite, a solid solution of Fe and 27 to 65% Ni. The Greek name means "without structure" and refers to the lack of a visible Widmanstätten pattern (spindles of kamacite are visible only microscopically). Click on Term to Read More. Tucson is highly reduced and might be related to the similarly reduced and Ge-depleted meteorites Santiago Papasquiero or Nedagolla. Nehru

et al. (1982) consider the likely precursor material of Tucson to have been a unique forsterite–enstatite silicate assemblage thus far unsampled as a meteorite, or perhaps it was a more forsterite-rich E chondrite-like body, although it has also been more recently proposed that Tucson may represent the most metal-rich and volatile-element-poor member of the CR

chondriteChondrites are the most common meteorites accounting for ~84% of falls. Chondrites are comprised mostly of Fe- and Mg-bearing silicate minerals (found in both chondrules and fine grained matrix), reduced Fe/Ni metal (found in various states like large blebs, small grains and/or even chondrule rims), and various refractory inclusions (such Click on Term to Read More clan.

A study of glass inclusions within and between olivines was conducted by Varela

et al. (2008, 2010). Olivine inclusions exhibit rounded surfaces in contact with

metalElement that readily forms cations and has metallic bonds; sometimes said to be similar to a cation in a cloud of electrons. The metals are one of the three groups of elements as distinguished by their ionization and bonding properties, along with the metalloids and nonmetals. A diagonal line drawn Click on Term to Read More, and crystal faces in contact with glass. Some investigators interpret the flow-like arrangement of the inclusions as indicative of a metallic melt intruding a silicate assemblage as a result of impact forces. On the other hand, ballistic aggregation is considered by some to be responsible for the elongated shapes and preferred direction of the silicates (Kurat

et al., 2010). In their studies of Tucson based on new petrographic evidence, Kurat

et al. (2010) found that metal and the Ca–Al–Si-rich liquid are early nebular condensates, which precipitated prior to the formation of the silicates. The silicates formed later from the Ca–Al–Si-rich liquid by vapor–liquid–solid condensation, in accord with the ‘primary liquid condensation’ model (Varela

et al., 2005; Varela and Kurat 2006, 2009). The glass phase is consistent with rapid quenching from the liquid phase, with a mineralogical composition consistent with derivation from

carbonaceous chondriteCarbonaceous chondrites represent the most primitive rock samples of our solar system. This rare (less than 5% of all meteorite falls) class of meteorites are a time capsule from the earliest days in the formation of our solar system. They are divided into the following compositional groups that, other than Click on Term to Read More material, especially CR

chondritesChondrites are the most common meteorites accounting for ~84% of falls. Chondrites are comprised mostly of Fe- and Mg-bearing silicate minerals (found in both chondrules and fine grained matrix), reduced Fe/Ni metal (found in various states like large blebs, small grains and/or even chondrule rims), and various refractory inclusions (such Click on Term to Read More; the composition is much different from that of enstatite chondrites.

In a similar manner, the O-isotopic composition of Tucson silicates and glass is similar to the CR clan and to Kakangari, and the low volatile

elementSubstance composed of atoms, each of which has the same atomic number (Z) and chemical properties. The chemical properties of an element are determined by the arrangement of the electrons in the various shells (specified by their quantum number) that surround the nucleus. In a neutral atom, the number of Click on Term to Read More abundances are also consistent with the CR clan. The Ca–Al–Si-rich glass in Tucson is also similar in trace element contents to those of carbonaceous chondrites, and they show unfractionated

REEOften abbreviated as “REE”, these 16 elements include (preceded by their atomic numbers): 21 scandium (Sc), 39 Yttrium (Y) and the 14 elements that comprise the lanthanides excluding 61 Promethium, an extremely rare and radioactive element. These elements show closely related geochemical behaviors associated with their filled 4f atomic orbital. Click on Term to Read More patterns. In addition, Tucson glass inclusions show many similarities to the glass in C chondrites and CR chondrites in particular. Beyond that, the metal component in Tucson has a highly refractory nature, in many ways similar to that of the IVA irons (Humayun, 2010). It is basically unfractionated and has probably inherited its trace element abundances and highly depleted volatile element content by direct condensation from an early solar

nebulaAn immense interstellar, diffuse cloud of gas and dust from which a central star and surrounding planets and planetesimals condense and accrete. The properties of nebulae vary enormously and depend on their composition as well as the environment in which they are situated. Emission nebula are powered by young, massive Click on Term to Read More gas, such as with CB and CH chondrites (Kurat

et al., 2010). A high-temperature nebular condensation origin is considered most plausible by investigators. A possible formation relationship between Tucson glasses and the glasses in IIE irons has also been conjectured.

A sub-mm-sized xenolithic

achondriteAn achondrite is a type of stony meteorite whose precursor was of chondritic origin and experienced metamorphic and igneous processes. They have a planetary or differentiated asteroidal origin where the chondritic parent body reached a sufficient size that through heating due to radioactive decay of 26Al (aluminum isotope) and gravitational Click on Term to Read More clastA mineral or rock fragment embedded in another rock. Click on Term to Read More from the

CM chondriteClass of carbonaceous chondrites named after the Mighei meteorite that fell in Ukraine in 1889. They represent samples of incompletely serpentinized primitive asteroids and have experience extremely complex histories. CM meteorites are generally petrologic level type 2 though a few examples of CM1 and CM1/2 also exist. Compared to CI Click on Term to Read More Mukundpura was analyzed by Ebert

et al. (2018). The clast has an O-isotopic composition and a REE pattern with HREE enrichment similar to silicate inclusions in the Tucson iron, and it is considered that they might share a common

parent bodyThe body from which a meteorite or meteoroid was derived prior to its ejection. Some parent bodies were destroyed early in the formation of our Solar System, while others like the asteroid 4-Vesta and Mars are still observable today. Click on Term to Read More (see diagram below).

click on image for a magnified view

click on image for a magnified view

Diagram credit: Ebert

et al., 81st MetSoc,

#6246 (2018)

A History Revealed

Each of the Tucson masses has a unique convoluted history. The first recovered and the largest of the two is the 1,400 pound (688 kg) ring-shaped mass, alternately called the Ring, Signet, Ainsa, and Irwin–Ainsa Meteorite at various times in history. The other mass, originally weighing 633 pounds (287 kg), is named the Carleton Meteorite for the Civil War general who appropriated the piece for public display.

The first written description of the Ring dates back to 1845. It was written in Spanish by a respected official of Sonora, Mexico, named José Velasco. From a section of his treatise concerning the state of Sonora, titled

Mines of Iron, Lead, Copper, and Quicksilver, he described a mountain pass (known today as Box Canyon) within the Sierra de la Madera range (now the Santa Rita Mountains). This pass, located between Tucson and Tubac, contained many large masses of pure iron, lying at the foot of the mountains. He wrote of a medium-sized mass that was taken to Tucson, a journey of over thirty rugged miles, where it had resided for many years [before 1845], serving as an anvil for the garrison armorer/blacksmith.

Writing in his diary for May 31, 1849, the ’49er A. Clarke clearly described the

findMeteorite not seen to fall, but recovered at some later date. For example, many finds from Antarctica fell 10,000 to 700,000 years ago. Click on Term to Read More circumstances and provided details of the appearance of the meteorite anvil used by the shoer of his mule. Shortly thereafter, in his article of 1852,

Notice of Meteoric Iron in the Mexican Province of Sonora, Dr. John LeConte described the appearance and recovery information of two meteoric anvils being used by blacksmiths in Tucson. That same year, in his diary entry for July 17, boundary commissioner John Bartlett described the origin and dimensions of the Ring mass and alluded to a second large mass located within the garrison in Tucson. He also made a detailed sketch of the celestial anvil, brought to light only in 1978.

Perhaps the most thorough description of the two masses was written by John Parke, lieutenant in charge of a survey expedition. He indicated that with much effort some small samples were acquired and sent to the east for analysis. An analysis was performed by Dr. Charles Shepard and published in 1854 in the American Journal of Science. He reported the lack of

crustOutermost layer of a differentiated planet, asteroid or moon, usually consisting of silicate rock and extending no more than 10s of km from the surface. The term is also applied to icy bodies, in which case it is composed of ices, frozen gases, and accumulated meteoritic material. On Earth, the Click on Term to Read More and the

oxidizedOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More nature of the meteorite sample, along with its chemical composition.

It was a blacksmith named Ramón Pacheco, who recovered the slab-like mass on or about 1850, and put it to use as an anvil in Tucson. In 1856, the other blacksmith anvil, the Ring, was abandoned leaving all the blacksmith duties to Pacheco and his anvil. In 1862, Colonel James Carleton confiscated the Pacheco anvil and had it shipped to San Francisco where permission was obtained to saw off a specimen for analysis. The mass remained on display at the Society of California Pioneers until 1939 when it was purchased by the Smithsonian to be displayed alongside the Ring mass.

During the year 1860, a medical officer named Bernard Irwin found the abandoned Ring mass and took possession of it on behalf of the Smithsonian. The following year, the meteorite was contracted to begin its journey from Arizona to Washington D.C. via Guaymas by Augustin Ainsa. He took two years to haul the mass to the coast, where his brother, Santiago Ainsa, took over the remaining leg to New York. Santiago was primarily interested in glorifying the family name and contrived a false history of the Ring mass in correspondence with the Smithsonian. In part, he claimed the mass was recovered by his famous great grandfather, Juan Bautista de Anza, in 1735 at a known location, and transported to Tucson. This legend, along with his other claims, have been proven to be totally fabricated; but not before the credit for the presentation of the Ring Meteorite to the Smithsonian was given to the Ainsas, including naming the Ring meteorite the Ainsa Meteorite.

When Irwin learned of this appalling turn of events, he sent a letter to the Smithsonian, debunking Ainsa’s fabricated story and protesting their choice of names for the mass. He stated he would rather they rename it the Tucson Meteorite rather than honor the fraudulent claims of Santiago Ainsa. After all, the Ainsas had only contracted to carry it to Washington for Irwin, the original donator to the Smithsonian. The name was subsequently changed to the Irwin–Ainsa Meteorite, but Irwin was intent on removing the name of Ainsa from the meteorite and publishing the correct history of the mass. It took twelve years for the name to be changed at Irwin’s insistence to the Tucson Meteorite.

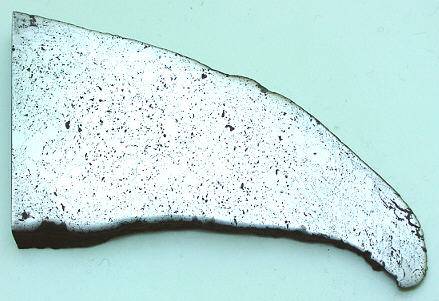

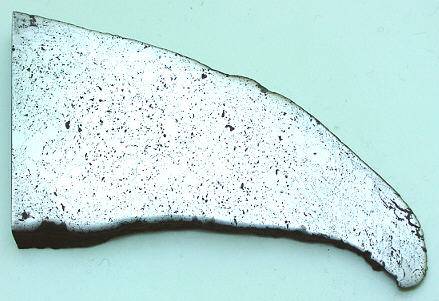

The 3.6 g specimen pictured above was originally part of the inner

nodule of the ring mass, and shows a polycrystalline structure with flow patterns of silicate inclusions. The Tucson Ring can be viewed today at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in the Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals.

Portions above excerpted from

The Tucson Meteorites by Richard R. Willey (1987)

A large part slice of Tucson.

Photo courtesy of the J. Piatek Collection

Tucson Ring and Carleton masses on display at the Smithsonian.

Photo courtesy of M. Horejsi