Whitecourt

Iron, IIIAB, octahedriteMost Common type of iron meteorite, composed mainly of taenite and kamacite and named for the octahedral (eight-sided) shape of the kamacite crystals. When sliced, polished and etched with an acid such as nitric acid, they display a characteristic Widmanstätten pattern. Spaces between larger kamacite and taenite plates are often Click on Term to Read More

Found July 1, 2007

53° 59′ 57′ N., 115° 35′ 51′ W. While searching with metalElement that readily forms cations and has metallic bonds; sometimes said to be similar to a cation in a cloud of electrons. The metals are one of the three groups of elements as distinguished by their ionization and bonding properties, along with the metalloids and nonmetals. A diagonal line drawn Click on Term to Read More detectors in a forested region near Whitecourt, Alberta, Canada, two local residents, James ‘Sonny’ Stevens and Rod Stevens uncovered four jagged, angular fragments of an iron meteoriteIron meteorites consist mostly of metallic iron alloyed with typically between ~5 to ~30 wt% nickel. The main metal phases are kamacite α-(Fe, Ni) and taenite y-(Fe, Ni). Based on their group classification, they may also contain a small weight percentage of one or more of the following minerals: • Click on Term to Read More. The fragments were located near the partially raised rim of a 36 m diameter, 5–10 m deep, circular impact crater of late Holocene age (<1,130 years old); the Whitecourt MeteoriteWork in progress. A solid natural object reaching a planet’s surface from interplanetary space. Solid portion of a meteoroid that survives its fall to Earth, or some other body. Meteorites are classified as stony meteorites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites. These groups are further divided according to their mineralogy and Click on Term to Read More Impact CraterCrater formed by high-speed impact of a meteoroid, asteroid, or comet on a solid surface. Craters are a common feature on most moons (an exception is Io), asteroids, and rocky planets, and range in size from a few cm to over 1,000 km across. There is a general morphological progression Click on Term to Read More is recorded in the Earth Impact Database, Planetary and Space Science Center, University of New Brunswick, Canada. The craterBowl-like depression ("crater" means "cup" in Latin) on the surface of a planet, moon, or asteroid. Craters range in size from a few centimeters to over 1,000 km across, and are mostly caused by impact or by volcanic activity, though some are due to cryovolcanism. Click on Term to Read More is now protected from meteorite hunting under the Alberta Provincial Historic Resources Designation Act.

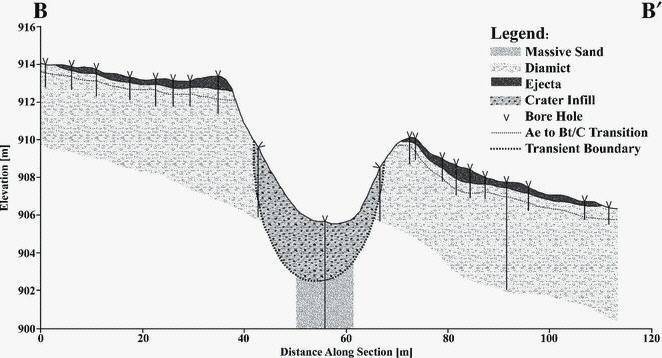

Cross section through the crater along 110°

Image credit: R. Kofman et al., MAPS, vol. 45, p. 1434 (2010)

‘The Whitecourt meteorite impact crater, Alberta, Canada’

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2010.01118.x) Calculations by Kofman et al. (2010) indicate that the Whitecourt crater was excavated by an impactor weighing 1,285–16,728 kg measuring ~0.7–1.6 m in diameter. By contrast, modeling conducted by Newman and Herd (2010) indicates a somewhat smaller object weighing 500–800 kg and measuring 0.5–0.55 m that impacted at 8–10 km per second from an angle of 55°. The target material was composed of sediments associated with the advance and retreat of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (Herd et al., 2008; Kofman et al., 2009). The impactor struck at an angle of 40–55° along a trajectory of 60–85°. Within the crater there is a sharp transition from poorly sorted, fine-grained glacial tillAn unconsolidated, poorly sorted sediment deposited by glaciers. Till contains rock and mineral fragments of all sizes from clay-size particles to massive boulders. (heterogeneous pebble diamict) overlying unconsolidated fine quartzComposed of SiO2, quartz is one of the silica group minerals most common in Earth's crust, but never found in meteorites as inclusions visible to the naked eye. Quartz in meteorites has been found in very small quantities in eucrites, other calcium-rich achondrites, and in the highly reduced E chondrites1. Click on Term to Read More sand at a depth of ~2.9 m, and it is considered that this boundary marks the base of the transient crater. Notably, amber-colored glass fragments are found above ~2.9 m (Kofman et al., 2008).

Simon de Boer standing in Whitecourt crater.

Photo courtesy of Simon de Boer (2010) Subsequent searches of the area have resulted in the recovery of more than 5,000 meteorite fragments, some found a considerable distance from the crater (Kofman et al., 2010; Newman and Herd, 2015). The meteorite fragments consist primarily of shrapnel-type morphologies but rare examples of regmaglypted individuals have been recovered. The smallest recovered fragment weighs 0.1 g and measures <1 cm in size, while the largest individual weighs 31.5 kg; the combined weight of both fragments and individuals is ~230 kg (Herd et al., 2008; Newman and Herd, 2015). It was reported that the largest mass was found at a depth of 61 cm. A 6.51 kg mass exhibiting regmaglypts and fusion crustMelted exterior of a meteorite that forms when it passes through Earth’s atmosphere. Friction with the air will raise a meteorite’s surface temperature upwards of 4800 K (8180 °F) and will melt (ablate) the surface minerals and flow backwards over the surface as shown in the Lafayette meteorite photograph below. Click on Term to Read More was found 261 m east-northeast of the crater. In addition, it has been reported that an exceptional mass weighing ~27 kg likely also retaining ablationGradual removal of the successive surface layers of a material through various processes. • The gradual removal and loss of meteoritic material by heating and vaporization as the meteoroid experiences frictional melting during its passage through the atmosphere. The resulting plasma ablates the meteor and, in cases where a meteor Click on Term to Read More features was found in the FallMeteorite seen to fall. Such meteorites are usually collected soon after falling and are not affected by terrestrial weathering (Weathering = 0). Beginning in 2014 (date needs confirmation), the NomComm adopted the use of the terms "probable fall" and "confirmed fall" to provide better insight into the meteorite's history. If Click on Term to Read More of 2010 and donated by the finders to the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Among other noteworthy fragments found outside of the protected zone is a 1.9 kg fragment that exhibits possible ablation characteristics. Diligent documentation of location, depth, weight, and other data for recovered fragments and individuals has made it possible to construct an accurate strewn fieldArea on the surface containing meteorites and fragments from a single fall. Also applied to the area covered by tektites, which are produced by large meteorite impacts. Strewnfields are often oval-shaped with the largest specimens found at one end. Given that the largest specimens go the greatest distance, a meteoroid's map:

Distribution of meteorites in and around the 200 × 200 m zone protected by the Alberta Historic Resources Law

Image credit: J. Newman and C. Herd, MAPS, vol. 50, #2, p. 310 (2015)

‘Mineralogy, petrologyScience dealing with the origin, history, occurrence, chemical composition, structure and classification of rocks. Click on Term to Read More, and distribution of meteorites at the Whitecourt crater, Alberta, Canada’

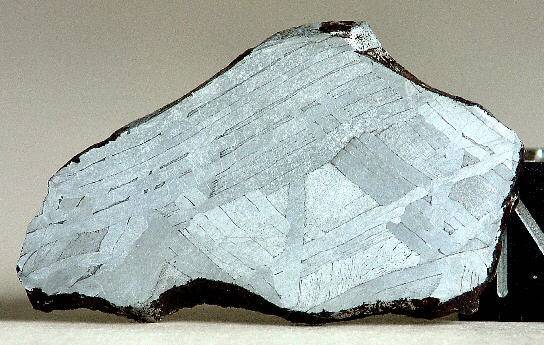

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/maps.12422) The crater is surrounded by an ejecta blanketGenerally symmetrical apron of ejecta surrounding a crater; it is thick at the crater's rim and thin to discontinuous at the blanket's outer edge. Click on Term to Read More covering 6,000 m² constituting 40% of the volume of the crater. Meteorite fragments recovered from under the ejectaFractured and/or molten rocky debris thrown out of a crater during a meteorite impact event, or, alternatively, material, including ash, lapilli, and bombs, erupted from a volcano. Click on Term to Read More blanket have experienced less oxidationOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More than those recovered from within the crater. It is thought that the crater was excavated during a high-angle, low-energy, hypervelocity impact by a single projectile measuring ~1.1 m in diameter traveling towards the east-northeast (Kofman et al., 2009). It was argued by Kofman et al. (2010) that the evidence was most consistent with a meteoroidSmall rocky or metallic object in orbit around the Sun (or another star). traveling 4–10 km per second which experienced a catastrophic disruption upon impact; the lack of size-sorting of the fragments and individuals is consistent with this scenario. Following the recovery of additional regmaglypted samples, some low-altitude fragmentation is considered to have occurred (Newman and Herd, 2015). Geochemical analyses and structural studies (conducted after etching) distinguish Whitecourt as a low-Ni medium octahedrite belonging to the IIIAB (IIIA) iron group (Herd, University of Alberta). Accessory minerals present in Whitecourt include a variety of sulfides and phosphides, along with rare chromiteBrownish-black oxide of chromium and iron (Cr-Fe oxide), Cr2FeO4, found in many meteorite groups. Click on Term to Read More inclusions and grains of carlsbergite and native copper (Newman and Herd, 2015). The iron meteorite shows some signs of shock and recrystallization, while planar microstructures present in quartz grains located below the transient crater boundary provide evidence for a low degree of shock. This is consistent with the presence of Fe,Ni-oxide spherules and rare samples of partially melted impactor material. The specimen of Whitecourt shown above is a 10.2 g shrapnel-type fragment kindly donated to dweir’s Meteorite Studies by its finder Simon de Boer, via Canadian Cultural Property Export Permit #103306. Pictured below is a Whitecourt slice that was expertly etched by Mirko Graul.

Photo courtesy of Mirko Graul Meteorite

See the ‘Meteorite Men’ episode Return to Whitecourt, 12 December 2011, originally broadcast on the Science Channel and now available on YouTube.