LL5

Fell February 17, 1930

36° 4′ N., 90° 30′ W. At about 4:00 in the morning, a bright fireballA fireball is another term for a very bright meteor, generally brighter than magnitude -4, which is about the same magnitude of the planet Venus as seen in the morning or evening sky. A bolide is a special type of fireball which explodes in a bright terminal flash at its end, often with visible fragmentation. Click on Term to Read More with accompanying detonations pierced the predawn sky, its path visible over several states. Some witnesses believed it to be a crashing airplane, but it was a meteoriteWork in progress. A solid natural object reaching a planet’s surface from interplanetary space. Solid portion of a meteoroid that survives its fall to Earth, or some other body. Meteorites are classified as stony meteorites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites. These groups are further divided according to their mineralogy and Click on Term to Read More that ended its fallMeteorite seen to fall. Such meteorites are usually collected soon after falling and are not affected by terrestrial weathering (Weathering = 0). Beginning in 2014 (date needs confirmation), the NomComm adopted the use of the terms "probable fall" and "confirmed fall" to provide better insight into the meteorite's history. If Click on Term to Read More near Paragould, Arkansas. The first stone that was discovered was found by farmer Raymond Parkinson at the bottom of a 3½ foot hole, southwest of Finch in the Poland Township. Three men spent half the following day digging the 80-pound stone out of Parkinson’s pasture. Parkinson sent a sample to H. H. Nininger asking if he would like to purchase the meteorite, but before Nininger could complete the trip, the stone was covertly sold by local high school teacher L.V. Rhine, to which it was on loan for exhibit. Nevertheless, while he was in the area, Nininger was able to calculate the meteorite’s trajectory and arrange for the purchase of any additional masses that he suspected might eventually be found.

Four weeks later, an 820-pound mass was discovered three miles from the first mass, and within 300 yards of a farmhouse. The mass was found lying in a

craterBowl-like depression ("crater" means "cup" in Latin) on the surface of a planet, moon, or asteroid. Craters range in size from a few centimeters to over 1,000 km across, and are mostly caused by impact or by volcanic activity, though some are due to cryovolcanism. Click on Term to Read More eight feet wide and eight feet deep. It was presumed by the homeowner, J. Fletcher, that the large hole had been dug by dogs, but its true nature was quickly realized by his neighbor, W. Hodges. The removal of the mass took three hours and required five men and a team of horses. The 820-pound mass was purchased by Nininger for the large sum of $3,600 and subsequently sold to the Chicago Field Museum for $6,200.

Prior to the events surrounding the fall and recovery of the Paragould meteorite, Nininger was forced to balance his passion for finding meteorites with his necessity for earning a regular salary, which he accomplished by teaching biology and geology at McPherson College in Kansas. The profitable sale of the Paragould

main massLargest fragment of a meteorite, typically at the time of recovery. Meteorites are commonly cut, sliced or sometimes broken thus reducing the size of the main mass and the resulting largest specimen is called the "largest known mass". Click on Term to Read More to Stanley Field and its subsequent donation to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago became the impetus for him to resign from his teaching job and dedicate his life full-time to the search for meteorites, ultimately becoming the most successful meteorite hunter of the century. The following quote from his book

FindMeteorite not seen to fall, but recovered at some later date. For example, many finds from Antarctica fell 10,000 to 700,000 years ago. Click on Term to Read More A Falling StarSelf-luminous object held together by its own self-gravity. Often refers to those objects which generate energy from nuclear reactions occurring at their cores, but may also be applied to stellar remnants such as neutron stars. is telling: ‘The Paragould meteorite had profound effects on our lives. I have never ceased to regret parting with it, but I had paid a price too high, and was forced to give up either the specimen or my dream of making meteorites a new vocation. And Paragould, with the $2,000 profit it brought, was the way to my dream.’ The 80-pound Paragould stone was purchased by Stuart Perry for his collection and then donated it to the Smithsonian National Collection in 1935. At the time of its fall, the Paragould meteorite was the largest known witnessed fall and the largest intact

stony meteoriteMeteorite composed of silicate minerals, but that may have up to 25% Ni-Fe metal by weight. Stony meteorites are extremely heterogeneous as a group, ranging from samples of primordial matter that have remained more or less unchanged for the last 4.56 Ga (chondrites) to highly evolved younger rocks from differentiated in existence. It has been highly shocked (S4–5) causing

plagioclaseAlso referred to as the plagioclase feldspar series. Plagioclase is a common rock-forming series of feldspar minerals containing a continuous solid solution of calcium and sodium: (Na1-x,Cax)(Alx+1,Si1-x)Si2O8 where x = 0 to 1. The Ca-rich end-member is called anorthite (pure anorthite has formula: CaAl2Si2O8) and the Na-rich end-member is albite Click on Term to Read More to recrystallize, resulting in a wide range of An compositions (A. Rubin, 1992; A. Brearley and R. Jones, 1998). The rare identification of L-chondrite clasts in the Paragould

brecciaWork in Progress ... A rock that is a mechanical mixture of different minerals and/or rock fragments (clasts). A breccia may also be distinguished by the origin of its clasts: (monomict breccia: monogenetic or monolithologic, and polymict breccia: polygenetic or polylithologic). The proportions of these fragments within the unbrecciated material Click on Term to Read More has been reported by Fodor and Keil (1978).

The photo above shows a 2.374 g partial slice of Paragould that was removed from the 820 pound mass which once belonged to H. H. Nininger. A magnificent

Paragould section can be seen on display at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

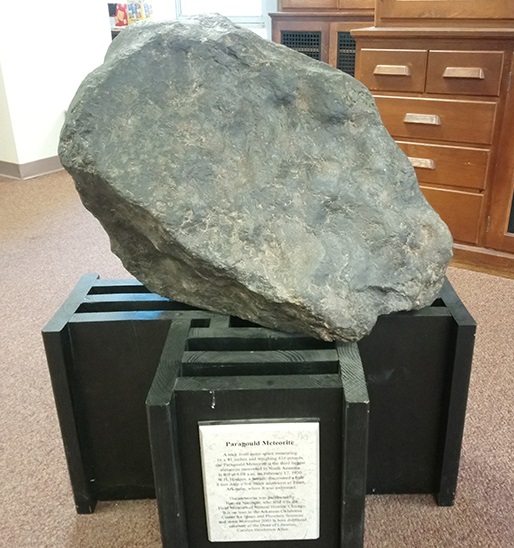

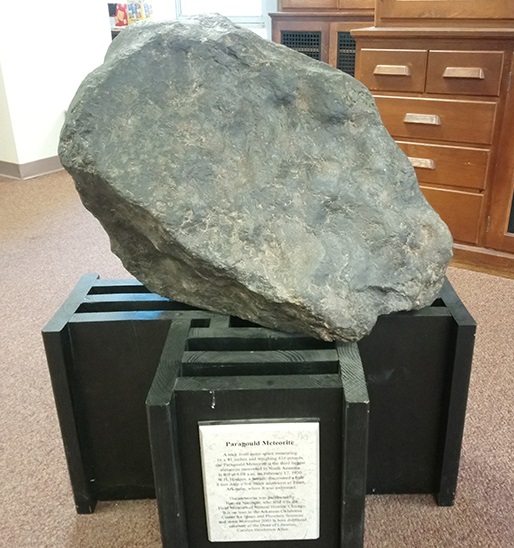

Paragould main mass on display in Mullins Library at the University of Arkansas