LODRAN

LodraniteRare type of primitive achondrite named after the Lodran meteorite that fell in Pakistan in 1868. Initially, lodranites were grouped with the stony-iron meteorites because they contain silicates (olivine, orthopyroxene, and minor plagioclase) and Fe-Ni metal in nearly equal proportions. However, since discovery of the closely related acapulcoite group, lodranites Click on Term to Read More

Acapulcoite–Lodranite Clan

click on photo for a magnified view Fell October 1, 1868

29° 32′ N., 71° 48′ E. This rare meteoriteWork in progress. A solid natural object reaching a planet’s surface from interplanetary space. Solid portion of a meteoroid that survives its fall to Earth, or some other body. Meteorites are classified as stony meteorites, iron meteorites, and stony-iron meteorites. These groups are further divided according to their mineralogy and Click on Term to Read More fell at 2:00 P.M. about 12 miles east of Lodhran, Pakistan. About 1 kg was preserved but the ~700 g main massLargest fragment of a meteorite, typically at the time of recovery. Meteorites are commonly cut, sliced or sometimes broken thus reducing the size of the main mass and the resulting largest specimen is called the "largest known mass". Click on Term to Read More in the Museum of Geology in Calcutta, India has been missing for some years. About 150 g is distributed among a few major museum collections, and a small amount exists in private collections.

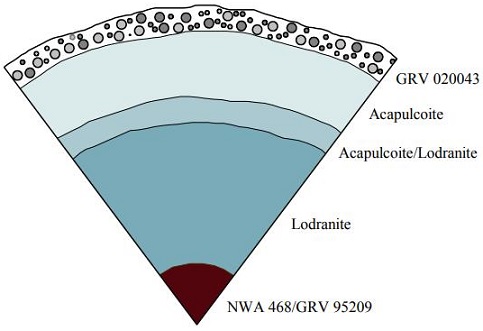

Diagram credit: Neumann et al., 49th LPSC, #1170 (2018)

Full article in Icarus, ‘Modeling the evolution of the parent body of acapulcoites and lodranites: A case study for partially differentiated asteroids’

(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.024) The precursor material of the acapulcoite–lodranite clan is thought by some to have been similar to CR or K chondritesChondrites are the most common meteorites accounting for ~84% of falls. Chondrites are comprised mostly of Fe- and Mg-bearing silicate minerals (found in both chondrules and fine grained matrix), reduced Fe/Ni metal (found in various states like large blebs, small grains and/or even chondrule rims), and various refractory inclusions (such Click on Term to Read More, with radiogenic heating within the parent body reaching temperatures high enough to produce partial melting without significant differentiation. A linkage between acapulcoite–lodranite achondrites and the CR clan meteorites was considered by Lee (2008) based on similarities related to chondruleRoughly spherical aggregate of coarse crystals formed from the rapid cooling and solidification of a melt at ~1400 ° C. Large numbers of chondrules are found in all chondrites except for the CI group of carbonaceous chondrites. Chondrules are typically 0.5-2 mm in diameter and are usually composed of olivine Click on Term to Read More size, formation age, Hf–W systematics, and O-isotopic range. On the other hand, siderophile elementLiterally, "iron-loving" element that tends to be concentrated in Fe-Ni metal rather than in silicate; these are Fe, Co, Ni, Mo, Re, Au, and PGE. These elements are relatively common in undifferentiated meteorites, and, in differentiated asteroids and planets, are found in the metal-rich cores and, consequently, extremely rare on abundances in the magnetic components in acapulcoites, as well as lithophile elementElement that tends to be concentrated in the silicate phase, e.g., B, O, halogens, alkali earths, alkali metals, Al, Si, Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Y, Zr, Nb, REE, Hf, Ta, W, Th, and U. abundances in non-magnetic components, led Hidaka et al. (2012) to conclude that the precursor material of the acapulcoite–lodranite group was most similar to EL chondrites. Schrader et al. (2017) observed an absence of chromite grains in relict chondrulesRoughly spherical aggregate of coarse crystals formed from the rapid cooling and solidification of a melt at ~1400 ° C. Large numbers of chondrules are found in all chondrites except for the CI group of carbonaceous chondrites. Chondrules are typically 0.5-2 mm in diameter and are usually composed of olivine Click on Term to Read More from acapulcoite GRA 98028. They recognized that chromite grains are only present in type II chondrules, and that these chondrules occur in greatest abundance in ordinary chondrites and are less abundant in carbonaceous and enstatiteA mineral that is composed of Mg-rich pyroxene, MgSiO3. It is the magnesium endmember of the pyroxene silicate mineral series - enstatite (MgSiO3) to ferrosilite (FeSiO3). Click on Term to Read More chondrites. Based on this reasoning, as well as other data, they consider it likely that the precursor of the acapulcoite–lodranite clan was similar to a carbonaceous chondriteCarbonaceous chondrites represent the most primitive rock samples of our solar system. This rare (less than 5% of all meteorite falls) class of meteorites are a time capsule from the earliest days in the formation of our solar system. They are divided into the following compositional groups that, other than Click on Term to Read More of a type unknown in our collections. Conversely, Keil and McCoy (2017) consider an S-type asteroid to be the most likely parental source object. Presolar s-process nucleosynthetic isotopeOne of two or more atoms with the same atomic number (Z), but different mass (A). For example, hydrogen has three isotopes: 1H, 2H (deuterium), and 3H (tritium). Different isotopes of a given element have different numbers of neutrons in the nucleus. Click on Term to Read More anomalies present in meteorites have been utilized to distinguish whether a parent body accreted in the carbonaceous or the non-carbonaceous reservoir. These two isotopic reservoirs represented the outer and inner Solar SystemThe Sun and set of objects orbiting around it including planets and their moons and rings, asteroids, comets, and meteoroids., respectively, and were separated by the growing gas giant Jupiter. Budde et al. (2018) determined the Mo isotope systematics for a sample from the acapulcoite–lodranite clan, and it was demonstrated that this parent body accreted in the inner solar systemDefinable part of the universe that can be open, closed, or isolated. An open system exchanges both matter and energy with its surroundings. A closed system can only exchange energy with its surroundings; it has walls through which heat can pass. An isolated system cannot exchange energy or matter with with other non-carbonaceous bodies (see diagram below).

Diagram credit: Budde et al., 49th LPSC, #2353 (2018) The total Fe content and Fe/Ni ratios in maficOne of the two broad categories of silicate minerals, the other being felsic, based on its magnesium (Mg) and/or iron (Fe) content. Mafic indicates silicate minerals that are predominantly comprised of Mg and/or Fe.The term is derived from those major constituents: Magnesium + Ferrum (Latin for iron) + ic (having Click on Term to Read More silicates are intermediate between those of ordinary and enstatite (EL) chondrites. Likewise, trace elementSubstance composed of atoms, each of which has the same atomic number (Z) and chemical properties. The chemical properties of an element are determined by the arrangement of the electrons in the various shells (specified by their quantum number) that surround the nucleus. In a neutral atom, the number of Click on Term to Read More compositions were found to support an origin on a body having characteristics of both H and E chondrites (Fukuoka et al., 1978). In a study of C in lodranites and acapulcoites, Charon et al. (2010, 2012) found that both C and N isotopic systematics for lodranites and acapulcoites, as well as the degree of C ordering among them, resembles that present in the insoluble organicPertaining to C-containing compounds. Organic compounds can be formed by both biological and non-biological (abiotic) processes. Click on Term to Read More matter (IOM) of CI–CM chondrites. This suggests an exogenous origin for the IOM of lodranites and acapulcoites from impact of a CI or CM body. In a synthesis of available data for acapuloites and lodranites, Eugster and Lorenzetti (2005) developed a model of the structure of the acapulcoite/lodranite parent body. They propose a layered ‘onion-shell’ structure not unlike that proposed for the ordinary chondrite asteroids, but one which was larger and experienced higher temperatures necessary for partial melting. Alternatively, a relatively small parent body might have begun its accretion very early while radiogenic 26Al was most prevalent, within a few m.y. of CAISub-millimeter to centimeter-sized amorphous objects found typically in carbonaceous chondrites and ranging in color from white to greyish white and even light pink. CAIs have occasionally been found in ordinary chondrites, such as the L3.00 chondrite, NWA 8276 (Sara Russell, 2016). CAIs are also known as refractory inclusions since they Click on Term to Read More formation. The Hf–W isochron indicates that the age of differentiation was ~5–6 m.y. after CAI formation, corresponding to an absolute age of 4.563 (±0.0009) b.y., which may be indicative of a much larger diameter body that retained its heat until well after most of the 26Al had decayed, at least ~3 m.y. after CAI formation. The typical acapulcoite material is thought to have originated in the outermost layer of the asteroid, which cooled earlier and faster consistent with its older gas retention age, finer-grain size, and less intense metamorphism (<1–3% silicate partial melting) as compared to the lodranites. The lodranite material formed within a hotter, deeper layer, experiencing a moderate degree of silicate partial melting (~5–20%) with loss of an FeS and a basaltic component (Bild and Wasson, 1976). The transitional acapulcoites exhibit features (e.g., HSE-rich metalElement that readily forms cations and has metallic bonds; sometimes said to be similar to a cation in a cloud of electrons. The metals are one of the three groups of elements as distinguished by their ionization and bonding properties, along with the metalloids and nonmetals. A diagonal line drawn Click on Term to Read More) consistent with extensive melting of metal and sulfide phases, including melt migration and pooling, representing a continuum between the formation of acapulcoites and lodranites, or alternatively, representing formation at greater depths associated with core formation (Dhaliwal et al., 2017). Based on multi-dimensional numerical models, a plausible thermal evolution for the acapulcoite/lodranite parent body was presented by Golabek et al. (2014). Accretion of the planetesimal began ~1.3 m.y. after CAI formation accompanied by the onset of radiogenic heating, primarily by 26Al. Over the succeeding ~3–4 m.y. temperatures increased from both radiogenic and impact heating until incipient metal–silicate segregation began as reflected in the lodranites. In contrast to the relatively near-surface formation of the acapulcoites and lodranites, higher temperatures at greater depth may have led to the formation of a metallic core. A rapid cooling stage is recorded in these meteorites at 4.555 b.y. ago, considered to represent the collisional disruption of the planetesimal. This was followed by re-accretion and the begining of an extended period of slow cooling. The O-isotopic composition of the lodranite group is variable, and plots between the terrestrial fractionationConcentration or separation of one mineral, element, or isotope from an initially homogeneous system. Fractionation can occur as a mass-dependent or mass-independent process. Click on Term to Read More line and the carbonaceous chondrites. The lodranite MAC 88177, as well as the acapulcoites that have been analyzed, have O-isotopes, chemistry, and mineralogy very similar to that of the CR chondriteClass named for the Renazzo meteorite that fell in Italy in 1824, are similar to CMs in that they contain hydrous silicates, traces of water, and magnetite. The main difference is that CRs contain Ni-Fe metal and Fe sulfide that occurs in the black matrix and in the large chondrules Click on Term to Read More group, but some differences exist. Relict chondrules have been identified in several acapulcoites: a 2 mm radial pyroxeneA class of silicate (SiO3) minerals that form a solid solution between iron and magnesium and can contain up to 50% calcium. Pyroxenes are important rock forming minerals and critical to understanding igneous processes. For more detailed information, please read the Pyroxene Group article found in the Meteoritics & Classification category. Click on Term to Read More chondrule was found in Monument Draw, a few recrystallized barred olivine chondrules were found in Y-74063, numerous POP and PP chondrules are present in GRA 98028, and many radial pyroxene, granular olivine–pyroxene, and porphyritic olivine chondrules occur in Dhofar 1222; in addition, evidence exists for the presence of relict porphyritic chondrules in ALHA77081. Acapulcoites represent the likely precursor material that existed prior to the collisionally-induced melting phase, in which temperatures became high enough to produce a 1–3 vol% basaltic partial melt—short of silicate partial melting, but high enough to mobilize melts of metallic FeNi–FeS and phosphate. This was followed by up to 5% melt removal, with most of the partial melt being retained in its source region, manifested by µm- to cm-sized metal veins (as present in Monument Draw). Other pockets were subjected to more intense shock heating to the point where plagioclase and clinopyroxene formed silicate basaltic partial melts. After a 12–20+ vol% basaltic, magnesian partial melt was extracted from the source rock, the residual melt, now depleted in FeS, FeNi, plagioclase, and incompatible trace elements, cooled to form the lodranite material. The acapulcoites crystallized with a fine grain structure (~0.15–0.23 mm) due to both rapid cooling near the surface and the lack of silicate partial melt for continued grain growth. With graphiteOpaque form of carbon (C) found in some iron and ordinary chondrites and in ureilite meteorites. Each C atom is bonded to three others in a plane composed of fused hexagonal rings, just like those in aromatic hydrocarbons. The two known forms of graphite, α (hexagonal) and β (rhombohedral), have Click on Term to Read More as a likely reducingOxidation and reduction together are called redox (reduction and oxidation) and generally characterized by the transfer of electrons between chemical species, like molecules, atoms or ions, where one species undergoes oxidation, a loss of electrons, while another species undergoes reduction, a gain of electrons. This transfer of electrons between reactants Click on Term to Read More agent, the acapulcoites became enriched in metallic Fe at the expense of FeO (Rubin, 2006). A coarser grain structure (~0.54–0.70 mm) was formed in the lodranites due an extended cooling period at depth, aided by an abundance of silicate partial melt. However, with the many new members available to study, it is now evident that a continuum exists for the grainsizes of these two groups, and it has been proposed by Bunch et al. (2011) that an arbitrary group division is no longer justified; the term ‘acapulcoite–lodranite clan’ should therefore be applied to all members of the combined group. In some rocks, varying degrees of melting, melt removal, and melt mixing occurred forming such transitional acapulcoites as EET 84302, ALH A81187, each containing lithotypes intermediate between the acapulcoite and lodranite groups, as well as the metal-rich members NWA 468 and GRA 95209. The lodranite LEW 86220 contains two distinct lithologies representing an acapulcoite host that was intruded by a basaltic partial melt from the lodranite layer. The ACA–LOD clan member that represents the highest temperature silicate-rich melt, FRO 93001, formed through a high-degree partial melt (at least 35%). It contains coarser grains with abundant enstatite and preserves lodranitic xenoliths (Folco et al., 2006). The lodranite MAC 88177 represents a lithology that has been intruded by an FeS melt following the removal of a partial melt. Apparently, the acapulcoite–lodranite clan represents a continuum of thermal histories not easily partitioned into only two groups. A division of the acapulcoite–lodranite meteorites based on metamorphicRocks that have recrystallized in a solid state due to changes in temperature, pressure, and chemical environment. Click on Term to Read More stage was proposed by Floss (2000) and Patzer et al. (2003).

- primitive acapulcoites: near-chondritic (Se >12–13 ppmParts per million (106). Click on Term to Read More [degree of sulfide extraction])

- typical acapulcoites: Fe–Ni–FeS melting and some loss of sulfide (Se ~5–12 ppm)

- transitional acapulcoites: sulfide depletion and some loss of plagioclase (Se <5 ppm)

- lodranites: sulfide, metal, and plagioclase depletion (K <200 ppm [degree of plagioclase extraction])

- enriched acapulcoites (addition of feldspar-rich melt component)

Accretion of the acapulcoite–lodranite planetesimal began ~4.565 b.y. ago and was complete after only ~1 m.y. This was followed by heterogeneous heating by radioactive elements and impact shock heating to temperatures ranging from 980°C (Monument Draw) to 1170°C (Acapulco) to ~1250°C (Lodran). The cooling history of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body is varied and complex. Following the heating phase, which resulted in somewhat higher temperatures for lodranites (more deeply buried), both groups experienced a moderate cooling rate from peak metamorphic temperatures to about 600°C, at which time rapid cooling ensued until about 350°C, likely reflecting emplacement near the surface. At 300°C, a drastic decrease in the cooling rate was initiated until the temperature reached about 290°C. At this point a further sharp decrease in the cooling rate occurred until ~90°C was reached. This drastic change to very low cooling rates suggests an increase in the insulating regolith. In consideration of the I–Xe and Pb–Pb systems utilized by Crowther et al. (2009), the earliest this disruption could have occurred is 9.4 m.y. after CAI formation.

This complex cooling history may reflect the impact removal of a significant overburden, or the collisional breakup and reassembly of the acapulcoite–lodranite body. The parent body cooled to the Ar closure temperature ~4.51 b.y. ago for the acapulcoites and ~4.48 b.y. ago for the lodranites, reflecting the higher temperature and correspondingly longer cooling period of the lodranites. Identical I–Xe closure ages were calculated for both acapulcoite and lodranite samples by Crowther et al. (2009) to be 4.5582 b.y. relative to the Shallowater aubriteAubrites are named for the Aubres meteorite that fell in 1836 near Nyons, France. They are an evolved achondrite that is Ca-poor and composed mainly of enstatite (En100) and diopside (En50Wo50) with minor amounts of olivine (Fa0) and traces of plagioclase (An2-8). They contain large white crystals of enstatite as Click on Term to Read More (4.5627 ±0.0003 b.y.). This similarity in I–Xe closure ages is consistent with a very rapid cooling phase on the entire asteroid. A subsequent period of annealing resulted in recrystallization to produce equigranular textures and a loss of shock indicators (Rubin, 2007). A mean cosmic-ray exposure (CRE) age of ~5.5 (±0.9) m.y. was calculated for most of the lodranites (e.g., Eugster and Lorenzetti, 2005), and this age also coincides with that of virtually all of the acapulcoites (4.2–6.8 m.y.). Based on multiple chronometers and the measured CRE ages, it is considered that a single impact encompassing an area of a few km ejected most all of the meteorites constituting both groups (Neumann et al., 2018). Coincidentally, H-chondrite CRE ages coincide with the acapulcoite–lodranite CRE ages, possibly demonstrating disruption by common impactors. Notably, the chondrite Grove Mountains (GRV) 020043, initially classified as H4, is most similar to primitive achondrites of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body based on both its mineralogy and with respect to its O-isotopic composition. It was proposed that this meteorite represents the chondritic precursor of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body (Li et al., 2010; abstract. The differences that do exist, such as in the elements V, Cr, and Se, may be related to specific characteristics of the precursor phase (Hidaka et al., 2012). A comprehensive study of GRV 020043 and other related meteorites was subsequently conducted by Li et al. (2018), and they clearly demonstrated that the mineralogy, geochemistryStudy of the chemical composition of Earth and other planets, chemical processes and reactions that govern the composition of rocks and soils, and the cycles of matter and energy that transport Earth's chemical components in time and space. Click on Term to Read More, and O- and Cr-isotopic compositions of this meteorite support its reclassification as ‘Acapulcoite chondrite’, representing the chondritic, unmelted, outermost layer of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body. They also provided similar evidence that NWA 468 derives from the ACA–LOD parent body, which, along with the metal-rich lodranite GRA 95209 (NASA lab photo), are considered to represent the deepest lithology (early core segregation) of the parent body. A schematic representation of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body was presented by Li et al. (2018): Interior Structure of the Acapulcoite–Lodranite Parent Body

Schematic diagram credit: Li et al., GCA, vol. 242, p. 96 (2018)

‘Evidence for a Multilayered Internal Structure of the Chondritic Acapulcoite–Lodranite Parent Asteroid’

(https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2018.09.004) Based on reflectance spectra data and oxygen isotope values, the asteroids 2 Pallas and 21 Lutetia have each been considered as a potential candidate parent object for the acapulcoite–lodranite clan meteorites (Neumann et al., 2018). While 2 Pallas also has a similar diameter and densityMass of an object divided by its volume. Density is a characteristic property of a substance (rock vs. ice, e.g.). Some substances (like gases) are easily compressible and have different densities depending on how much pressure is exerted upon them. The Sun is composed of compressible gases and is much Click on Term to Read More to the optimized model of the AL parental asteroid, it follows that the much smaller 21 Lutetia would only represent a fragment derived from the original parent object. It is notable that the models employed by Neumann et al. (2018) indicate a small grain size (0.2 µm) for the precursor material of the AL parent body, consistent with a large matrixFine grained primary and silicate-rich material in chondrites that surrounds chondrules, refractory inclusions (like CAIs), breccia clasts and other constituents. Click on Term to Read More component. Considering the high matrix volume present in K chondrites, along with the mineralogical and geochemical data for that rare group, they speculated that the K chondrites might represent the thin chondritic outer layer of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body. For more information regarding the formation scenario of the acapulcoite–lodranite parent body, visit the Monument Draw page. The specimen shown above is a partial end section of the Lodran meteorite weighing 0.92 g and measuring 15 mm in its longest dimension. The photo shows a coarse grained aggregate with triple junctions, along with a metal component that had reached temperatures necessary for incipient melting prior to the onset of percolation. Below is a photo of a much larger specimen of Lodran curated at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

click on image for a magnified view

Photo courtesy of Martin Horejsi, c/o Smithsonian Institution